The world of fantasy is chock-full of characters who can do something special.

But I have to say, something I’ve found really enjoyable lately is creating characters who are at least partially defined by what they cannot do.

Imposing limits on a character can deepen them, make them more unique, and open the door for more original storytelling.

Allow me a few examples.

Ringo, the sidekick in Blue Eye Samurai, was born without hands. This begs the question: of what use could he possibly be to our hero, Mizu, a warrior on the path of revenge?

As it turns out, he can do quite a lot! It also makes him the ideal companion; in this story, Mizu’s “half-breed” blood makes her at least as deformed as Ringo, which in turn allows her to lean on him in a way she wouldn’t with anyone else (this also makes her character more accessible to the audience). More importantly, his sunny disposition, strength of character and sense of honor make Ringo the ideal teacher; he knows more about what it means to be samurai than 99% of the samurai around them. Lastly, his lack of hands makes him more like us; sure, most of us still have our hands, but we’re as useless with a katana as he is.

Dory, from Finding Nemo, follows a similar arc. Dory cannot retain short-term memory - a rather debilitating quirk! - but her optimism, bravery and resilience are exactly what Nemo’s father (anxious and haunted by memory) needs to grow. And this unique character aspect provides us with several amusing story beats.

Dory and Ringo are both, of course, sidekicks. But if we take Dory’s particular ailment even further (and quite a lot darker), we get Leonard Shelby, from Memento.

Shelby’s inability to store short-term memory defines not only his entire quest, but the very structure of the film. Memento, if you remember, is a film told entirely backwards - something few directors have ever attempted.

In Memento, the protagonist’s limit defines the structure of the film.

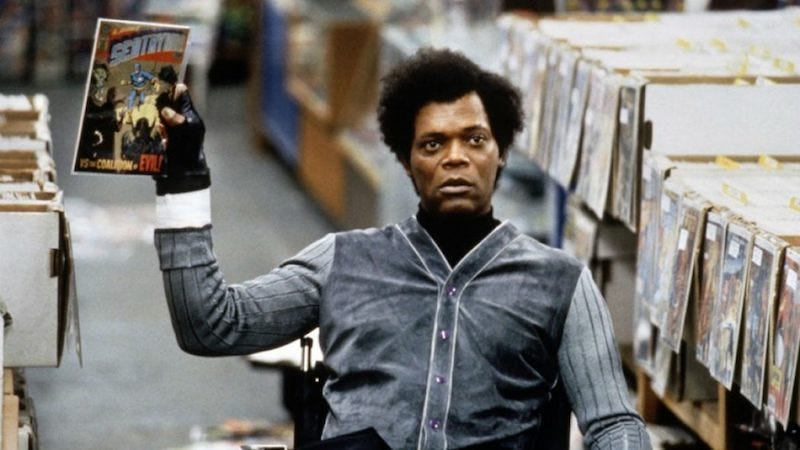

And if we go darker still, we get Elijah Price, aka Mr. Glass, the villain from Unbreakable.

The wheelchair-bound Mr. Glass has extremely breakable bones, and he has allowed this limit to, quite literally, define him. It is only because of his medical condition that the story can even begin, when he commits unspeakable atrocities in order to find his opposite, the hero David Dunn.

In Quiet: Level One, I’ve taken the idea of limits to the next level.

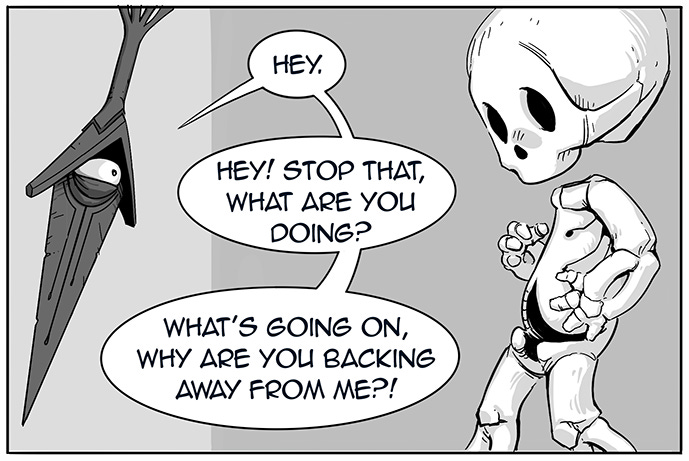

Our protagonist, Quiet, cannot speak. This means that, even if the situation desperately calls for words, they will be unable to deliver. This is going to be a huge impediment for them, and for me, but I am standing by this decision and I welcome the challenge.

To communicate this limit, I’ve drawn Quiet without a mouth (or even teeth, which was actually an aesthetic choice, since teeth are creepy).

Quiet’s sidekick, the Narrator Worm, can speak at length and with great eloquence about any number of topics… except itself. This unique quirk of its biology denies it the ability to even acknowledge its own existence.

The Narrator Worm has a mouth, to show that it can speak, but its arms are useless nubs. It has no eyes (nor can it say “I”), but this is designed to showcase its nature as a sometimes-Oracle.

(And from a plot-perspective, I’m excited by the possibilities. How does a Narrator help its Protagonist? How does it converse with others?)

Threadcutter’s limits are entirely physical; he is entirely dependent on others to help him get anywhere.

His furious eye is all-seeing - indeed, Threadcutter knows more about the Tree of Worlds (and how to bring it down) than anyone - but he cannot do anything for himself. I’ve communicated this by giving him an eye, a blade, and nothing else.

And Galahorn the almighty can do just about everything… but he can’t see the truth.

Like putting blinders on a horse, I’ve shielded his eyes in metal. While Threadcutter sees all, Galahorn can see nothing but the narrow path before him.

And now, to put on my own blinders, and get back to the art.

Happy Saturday friends!

Jonah

In one of my projects I had a character with a bit of a flaw; she wanted to help--she wanted to be the solution. Now that might not sound like much of a flaw, but when the other character uses it to draw her into the problem and keep her there...

This reminds me of an article I read years ago called Sandersons second law or something like that by author Brandon Sanderson, about how limitations are more interesting than abilities. That always stuck in my mind, so a post like this from any creator, is a huge green flag for me.