Rockets in Parallel

Of rains, planes, and personal demons

Whenever I hear the phrase “Character Arc,” I picture a rocket.

In the telling of a story, the hero’s journey really begins at the moment of ignition (called the “inciting incident”). At that moment, the rocket bursts free of its cradle, overcomes its earthly tethers, and goes roaring up into the atmosphere of The Story.

Lots of exciting things [should] happen as the rocket hurtles through the sky: there’s wind and rain, birds, planes, flying sharks, spiteful ex-lovers, interdimensional portals, and at least one major personal demon. As the rocket arcs back down to earth, the storm gets worse. As events unfold, the chaos worsens, until our rocket (red lights flashing, heat shields failing) shakes to the point of catastrophe.

At that moment (the end of Act 2 into Act 3, roughly), the question becomes not merely “Where will this rocket land?” but “Is this rocket about to explode?”

A good character - like a good rocket - is designed to get us from Point A to Point B (in the story). But the real meat of a good story is in the journey of the characters, and how the forces of the world - both inner and outer - change that journey along the way.

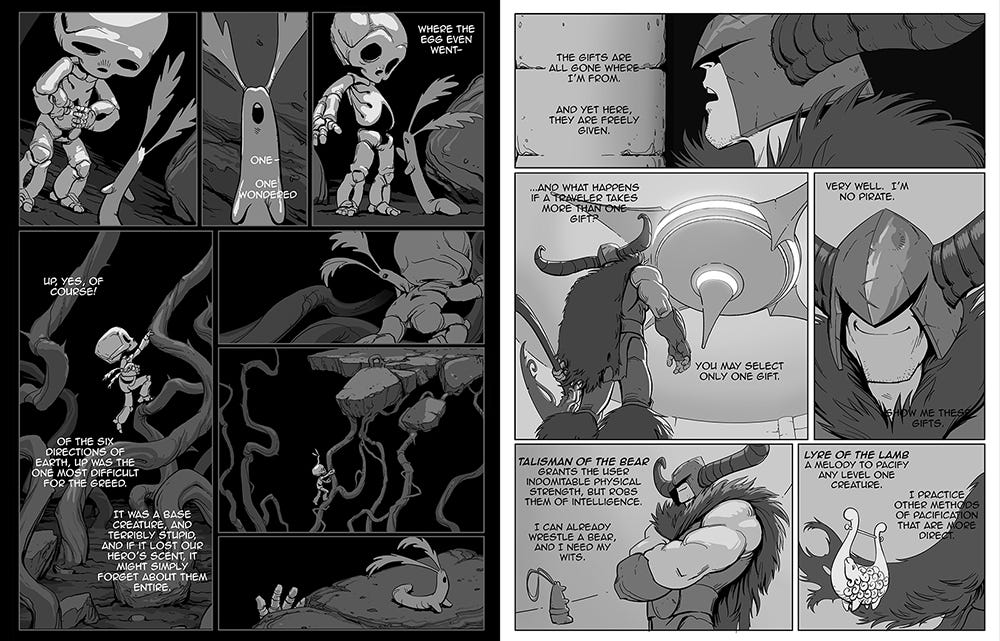

Quiet: Level One has two main characters.

Yes, Q:L1 is the story of a little skeleton’s quest to save the Tree of Worlds. So too is it the story of Galahorn and his quest to [redacted]. They are the two most important characters in my world, and they represent two sides of the very same story:

Quiet and Galahorn stand in diametric opposition, and the actions of one force the reactions of the other. They circle each other with the accelerating orbits of converging planets, but the storms they encounter will be very different in nature.

To ensure that their mostly separate quests compose a greater, more balanced narrative, I’ve been illustrating their stories in parallel. I bounce back and forth between consecutive scenes/chapters and try to establish greater flow and rhythm between them. I’m doing that through both the writing and the art.

For the writing, I try to balance each scene according to mood and speed. If one scene contains a lot of action, I’ll use the other to focus on something quieter: exposition, character building, or visual storytelling. In this way, I can [hopefully] create a ping-pong effect in the story, one that provides periods of action and equally-important periods of rest.

I do the same thing with the art. If one scene contains a lot of sharp, bold lines and angles, I’ll make the next scene softer and more regular. If one scene is dark, I’ll make the other one brighter. If this comic were in color, I’d adjust the color grading of each story to be a slightly different hue.

However, while I’m creating differences between each scene, I’m also factoring these differences through the lens of the entire story. While it’s critical that there be stylistic differences between Galahorn and Quiet’s stories, their two stories must blend together to form a unified whole. I don’t want too great a disparity between the mood and content of each consecutive scene; if the difference between them is too stark, it risks creating jarring emotional/narrative whiplash. The only times when this is truly appropriate is when I want to heighten drama and underscore the very different circumstances of my characters at a particular moment.

In my next article, we’ll talk about how this approach is also helping to keep me fresh. Large projects like videogames, novels, or comic books are journeys that require thoughtful planning, constant toil, and plenty of lembas bread.

The journey is long, but the project is fun, and it should never feel like drudgery.

Have a great day, friends.

Jonah

PS:

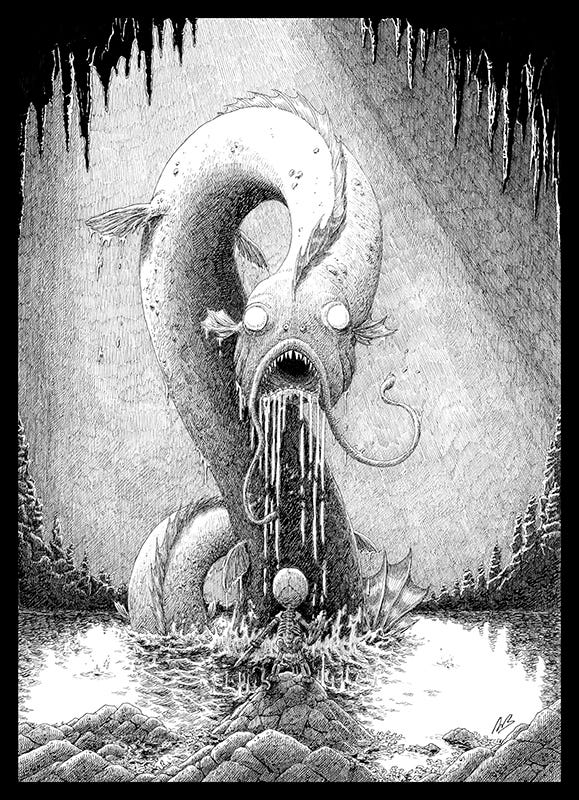

One of the artists I follow, Andreas von Buddenbrock, created a spectacular work of fanart for Quiet: Level One. Check it out:

Andreas also just published an art book, The Ink Trail: Hong Kong. I got a copy and have been geeking out at Andreas’ attention to detail. Fans of black-and-white art, this is for you!

A great read! And congratulations, Andreas!